Our friend Chuck (Master Gryphon), a talented wood worker, has been working on making replicas of the turned wooden box in which the three Rotterdam brooches were found. He has shared a step by step description of his process.

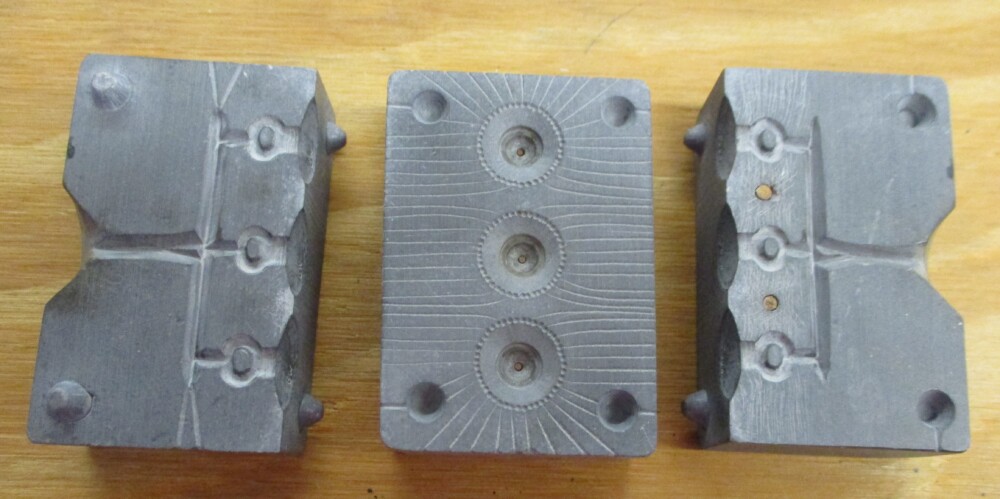

The Rotterdam trio, as we call them, are three brooches dated to 1350-1400. They were excavated from the construction site of the Markthal in 2009-1010 and when they were found, they were all in a single wooden box, barely large enough to hold them. Images of the brooches and the remains of the box were published in Heilig en Profaan 3 (2012).

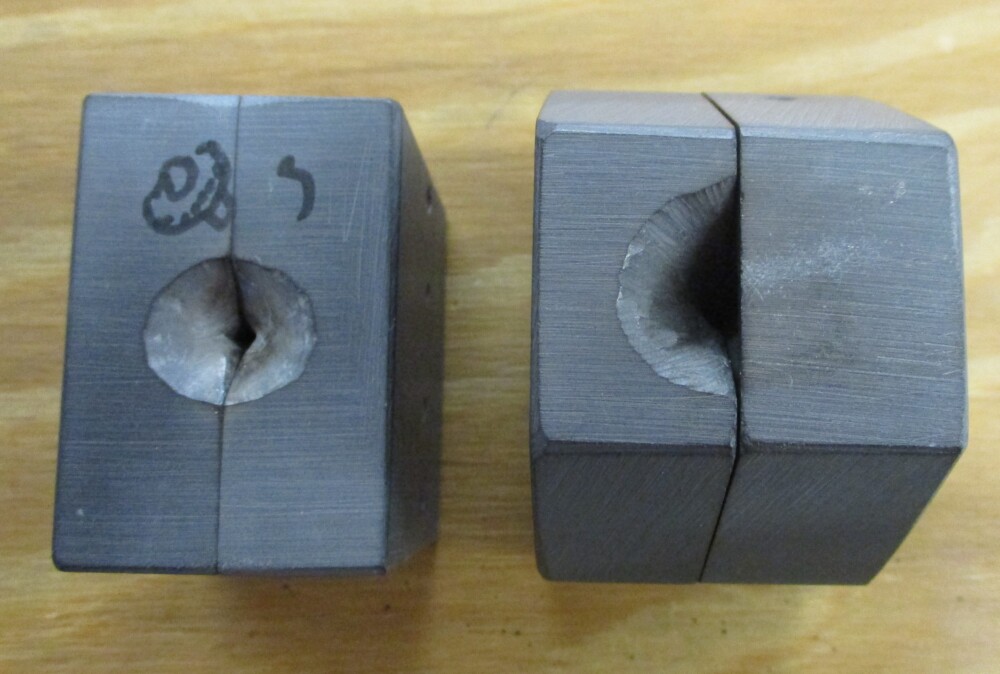

The kind folks at Archeologie Rotterdam (BOOR) provided better photos of the box (as well as images of the three brooches). They say that the wooden box is 2.7 cm high and approximately 3.0 cm in diameter.

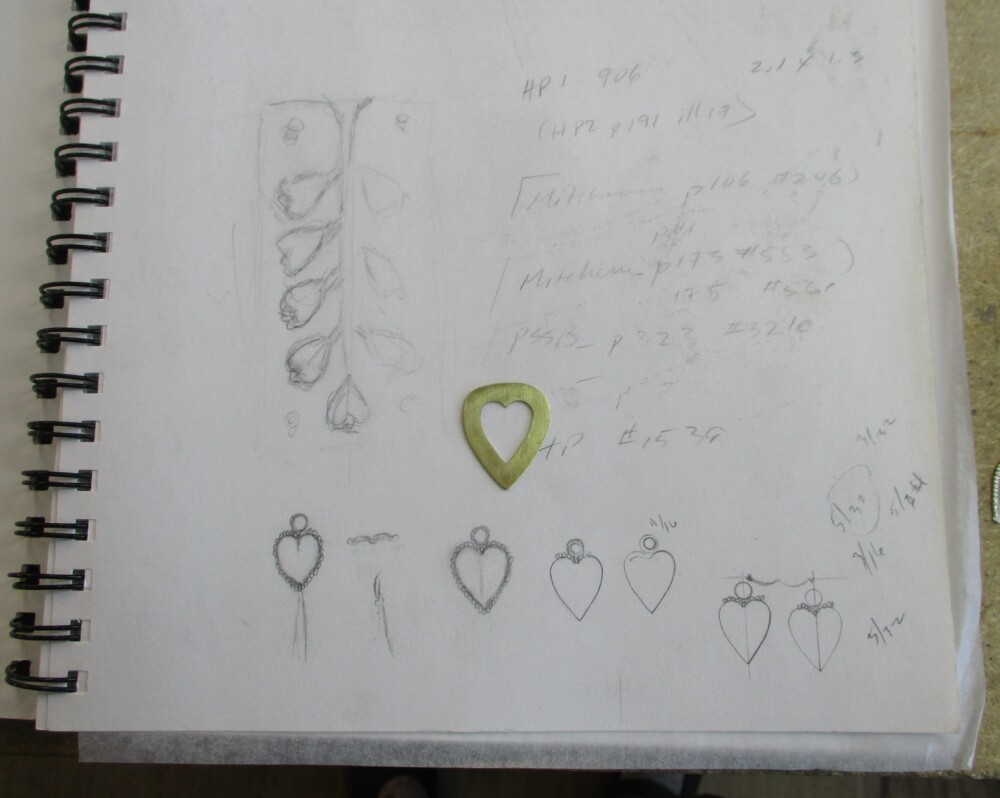

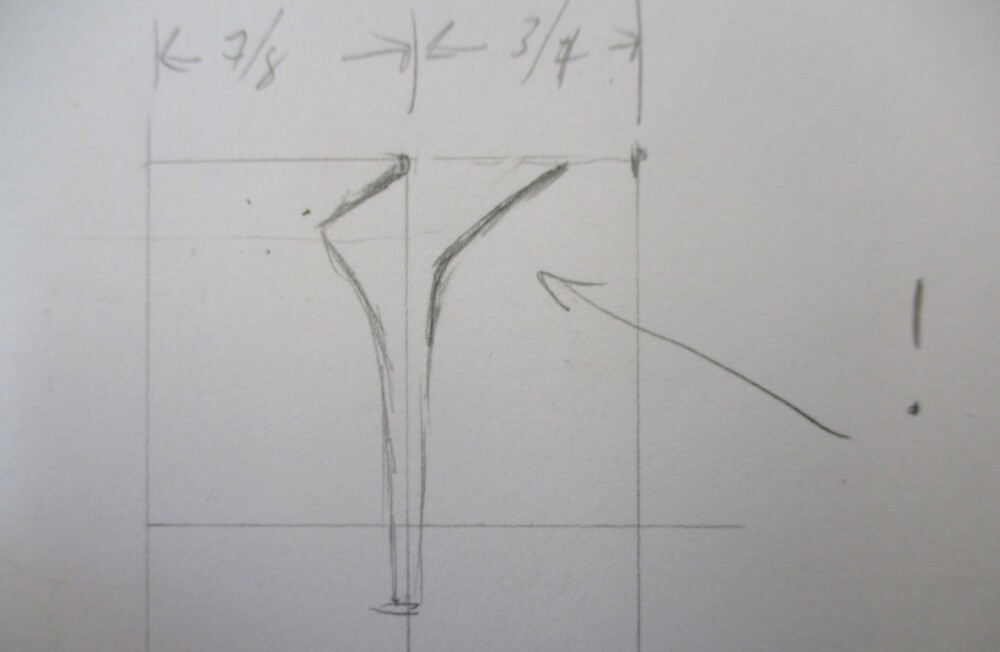

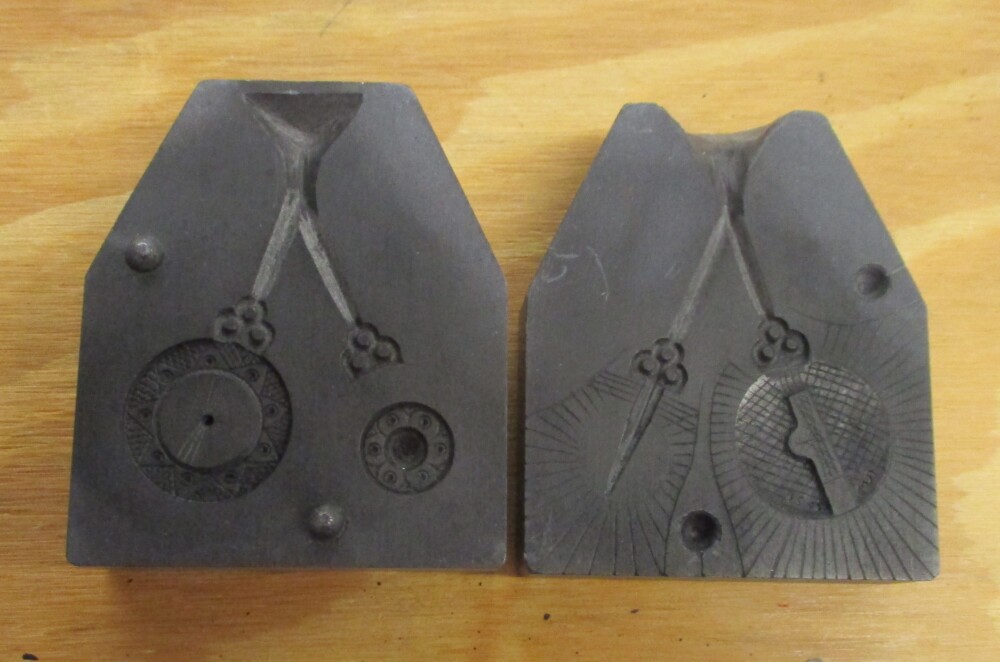

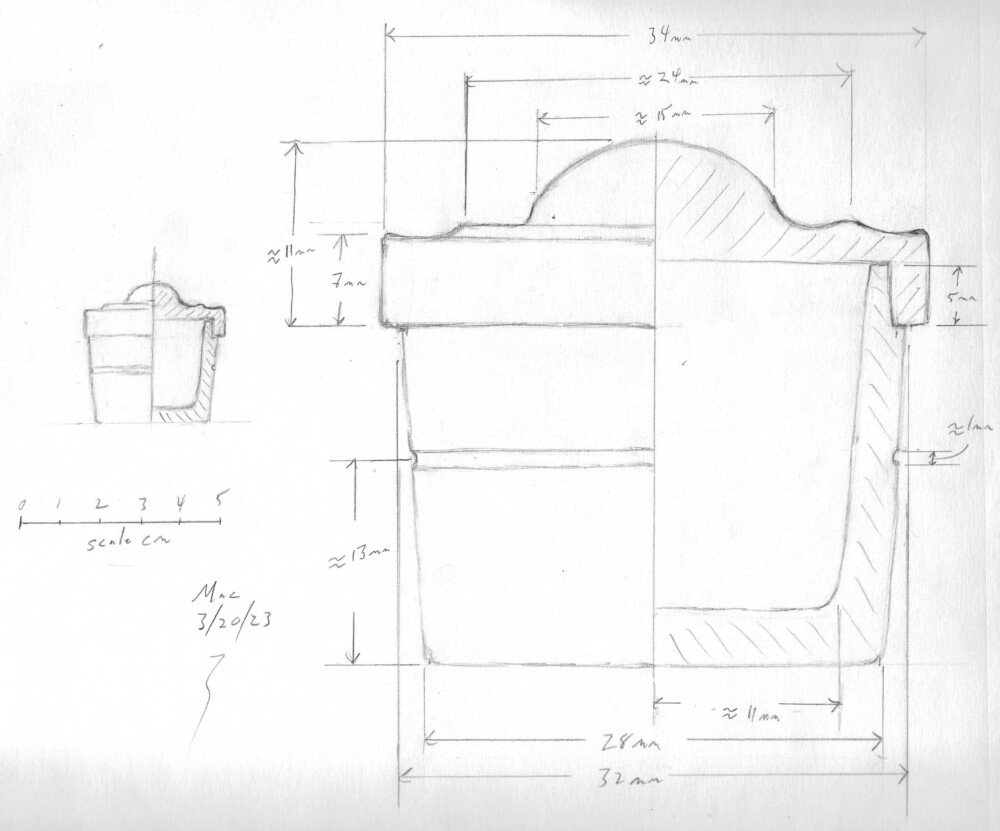

Chuck and Mac studied the photos, discussed where the measurements were taken, and talked about what the box might have looked like when it was complete. Mac made a sketch showing the results of their analysis.

After a series of experiments and test pieces, Chuck produced not only our box (and some additional boxes for friends), but also photos showing his procedure. He has been kind enough to share these:

Select a square piece of close grained hardwood at least 1.5” square x 6” long. Mount between centers on the lathe.

Turn round to just less than 1.5” diameter.

Use a 7/8” Forstner bit and drill in 21mm. Can also use bowl gouge or scraper instead of drill.

Check the depth for 21mm.

Use a round nose scraper (or bowl gouge) to shape the inside to the proper dimensions and taper (26mm at top and 22mm at bottom).

Place live center in opening.

Use spindle gouge to turn the outside to the proper dimensions, taper, and add lip for lid.

Use parting tool to cut to length leaving it still attached. Sand the inside and outside and finish parting from lathe.

Mark the remaining piece on the lathe for the top dimensions (7mm and 11mm) and turn the inside to match the lip on the bottom.

Insert the bottom into the top recess and check for tight fit.

Turn the top diameter to 34mm diameter and 11mm long.

Sand and part the top from the lathe.

Turn a recess into the remaining piece on the lathe to accept the bottom and act as a jam chuck. Check that the bottom is centered.

Mount the top onto the bottom.

Adjust the tail stock to lightly support the top mounted to the base.

Finish turning the outside of the top. Remove the small stud and sand.

The finished box.

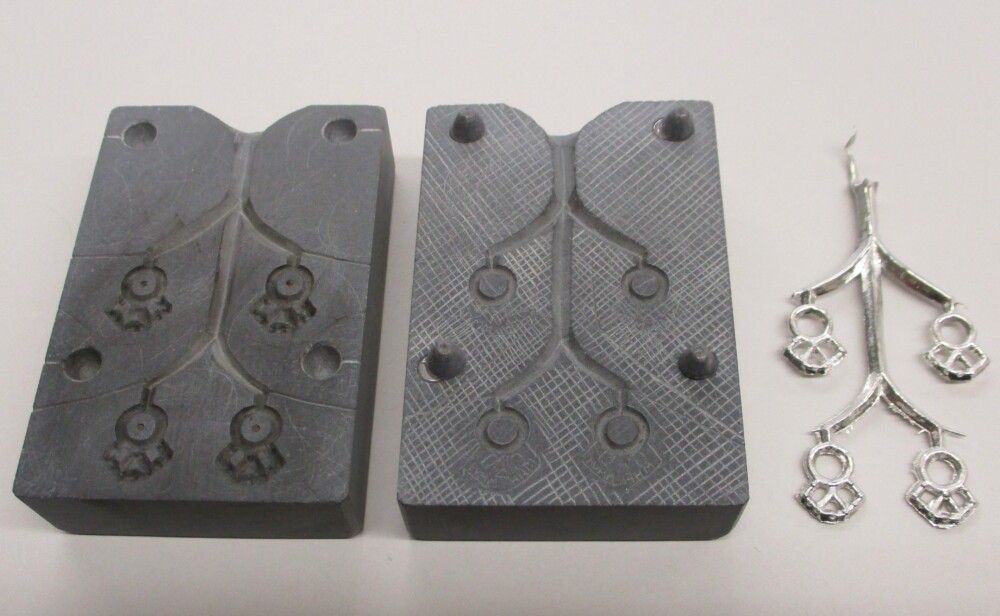

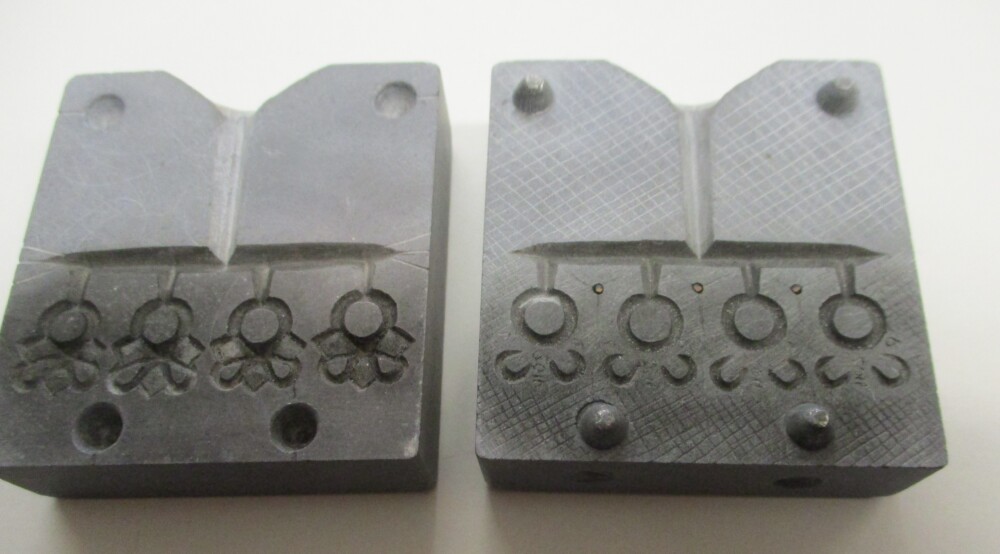

See our replicas of the brooches that were found in the original box.

Interested in seeing more boxes, both extant examples and in art? Mac has a Pinterest page on them.